BioSocial Health J. 1(2):64-73.

doi: 10.34172/bshj.21

Review Article

Gather together in the name of our next generation: A scoping review of the essence and implementation of community baby showers

Aysha Jawed Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1, *

Catherine Ehrhardt Writing – review & editing, 2

Molly Rye Writing – review & editing, 2

Amy Hess Writing – review & editing, 2

Elizabeth Murter Writing – review & editing, 2

Colin Gardiner Writing – review & editing, 3

Author information:

1Department of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, Baltimore, MD, USA

2Department of Pediatric Nursing, Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA

3School of Public Health, University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, MD 20742, USA

Abstract

Introduction:

Sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) collectively represent one of the leading causes of infant mortality worldwide. There are a range of evidence-based modifiable risk factors for both, particularly related to the infant’s sleep environment. Oftentimes, social determinants of health impact optimization of an infant’s sleep environment, thereby compromising their safety and elevating their risk for SIDS and SUID. Many kinds of community interventions that include campaigns and programs have sought to address these environmental modifiable risk factors that contribute towards heightened risk for SIDS and SUID. However given resource limitations, reach and access considerations, and scarcity of a streamlined harmonized process to draw on the strengths of a community in SUID and SIDS reduction, there is mixed success with these interventions.

Methods:

Although community baby showers are rising as a trending health promotion intervention to optimize access to care, resources and support to infants and their caregivers as well as optimize infant growth and development, there is no review paper to date that consolidates the strengths and limitations in the quality, delivery and evaluation of community baby showers as a continued focus for future public health interventions surrounding the infant population which informs the development of this scoping review.

Results:

Specifically, this review synthesizes the commonalities, differences, key findings, intervention components as well as gaps in research and practice on community baby showers across published studies (n=20) and secondary sources (n=4).

Conclusion:

Clinical and public health implications are also closely examined and further inform recommendations for future directions that draw on the strengths and build off the limitations of findings from this review to heighten the clinical and public health impact and further assess the efficacy of community baby showers as an evidence-based community engagement and health promotion intervention for our next generation of infants and their families.

Keywords: Community baby shower, Health promotion, Health education, Prevention, Sudden unexpected infant death, Sudden infant death syndrome, Infant mortality

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) remains a longstanding and leading cause of infant mortality worldwide.1-3 There are many causes for SUID including sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Although both SUID and SIDS constitute unexplained causes of infant death following comprehensive examination that includes autopsy and imaging of infant, oftentimes there are several modifiable risk factors that contribute to increased SIDS rates.4-6 These modifiable risk factors involve environmental determinants that include the infant’s sleep environment. Some of the most prevalent of these environmental risk factors are infant sleep surface, environmental tobacco exposure, overheating, co-sleeping / bed-sharing, inaccessibility to breastfeed, limited caregiver support among many more.5-8 Notably, these risk factors are evidence-based ones, as thoroughly researched and delineated in the American Academy of Pediatrics infant safe sleep guidelines.

Globally, assuring access to the range of services and resources that can effectively address these risk factors remains a longstanding public health complexity.1 One strategy to reach high risk regions could originate in the community. Campaigns and programs oftentimes have a national and community level presence. For example, the Safe-to-Sleep campaign and Cribs for Kids organization in the United States (U.S.) offer all states access to infant safe sleep resources that include educational and concrete environmental ones. Health departments variably provide access to resources that address modifiable risk factors for SIDS (e.g. safe sleep habitats), and WIC clinics also variably supply access to breast pumps for mothers in place of formula.9,10 However, evidence has consistently demonstrated that not everyone who could reap the benefits of these programs is able to participate. Furthermore, enrollment in some of these programs is limited to children and families with health insurance access and financial resources, which itself creates a health inequity.

A community baby shower presents an opportunity to account for the limitations of campaigns and programs and further increase reach and engagement across an entire community, not only in low-risk and moderate risk regions but also in higher risk regions. SUID and SIDs do not discriminate – in fact, infants from all different socioeconomic groups are affected. A community baby shower is a health promotion intervention that involves communication, collaboration and coordination among a range of community entities and stakeholders to optimize access and success to both new and experienced mothers and other caregivers involved in the care of infants.9 These community entities and stakeholders are already involved in the delivery of care, resources and services to the community residents. Each entity and stakeholder bring their own strengths and contributions to the community. Community entities include the local department of social services, faith-based organizations, schools, libraries, community centers, healthcare systems, laboratory testing services, drug stores, among many more. Tapping into the strengths of how each of these entities can contribute towards optimizing infant health from the onset is at the heart of community baby showers.

A public health intervention that involves health education, health promotion and accessibility of resources could likely most effectively address the range of social determinants of health that could be contributing towards increased morbidity and mortality for the range of longstanding public health issues which include homelessness, acute and chronic diseases, opioid crisis, and the mental health crisis. Infant mortality is no exception and finding ways to address the range of modifiable risk factors is one of our most pressing contemporary global health challenges in the infant population. Community level interventions that are transparent, replicable, feasible and cost effective with increased accessibility yield promise in reaching infants and their caregivers, both prenatally and postnatally to optimize longevity and quality of infant life and lay the foundation to support infant growth and development. Given limited coverage on community baby showers in comparison to campaigns and programs globally in addressing infant mortality, it is crucial to further conceptualize and critically examine community baby showers as a health promotion tool and intervention for this fragile population and their caregivers as their proxies.

Notably to date, there is no review paper that consolidates the key features in the design, implementation and evaluation of community baby showers as an integrated health education and health promotion intervention. Although there are many studies and secondary sources that have covered community baby showers, there are missing outcomes on their impact on health behavior change among caregivers of infants, heightened knowledge and awareness on infant health, feasibility of a community baby shower as an intervention, and direct impact on infant health outcomes. This review seeks to identify the commonalities and differences in the implementation of this community level intervention across studies and secondary sources worldwide. Further, this review also consolidates which outcomes have been covered thus far as part of the evaluation of community baby showers.

In turn, the primary goals of this review are the following: (1) synthesize features, characteristics and content covered across community baby showers in the published academic and lay literature; (2) identify gaps in current research and practice surrounding community baby showers in the health promotion landscape; (3) conceptualize the clinical and public health implications of community baby showers; and (4) present recommendations for future work that could draw on the strengths and build off the limitations of the community baby showers covered in this review.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

A scoping review of both academic literature and secondary sources on the development, implementation and evaluation of community baby showers as a public health intervention was conducted in April 2024. The medical, public health, and psychosocial databases reviewed were the following: PubMed, Medline, APA Psych Info, Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, ERIC, EBSCO, and Cochrane Review. Key phrases across searches pertained to singular and plural forms of community baby shower.

Eligibility criteria

Peer-reviewed journal articles and secondary sources were included in this review that involved either an analysis of prior community baby showers retrospectively or the delivery, implementation, and evaluation of community baby showers prospectively. Any articles that did not cover community baby showers as an integral intervention component or standalone intervention were excluded from this review.

Procedure

Six authors independently reviewed all titles and abstracts across each selected database. Any differences concerning full-text inclusion were resolved through group consensus. The authors then independently abstracted data across all included academic and secondary sources on the content of community baby showers covered as a public health intervention. Findings were subsequently compared and discrepancies in perspectives and analyses of content were resolved through active discussions amongst the group of authors.

Results

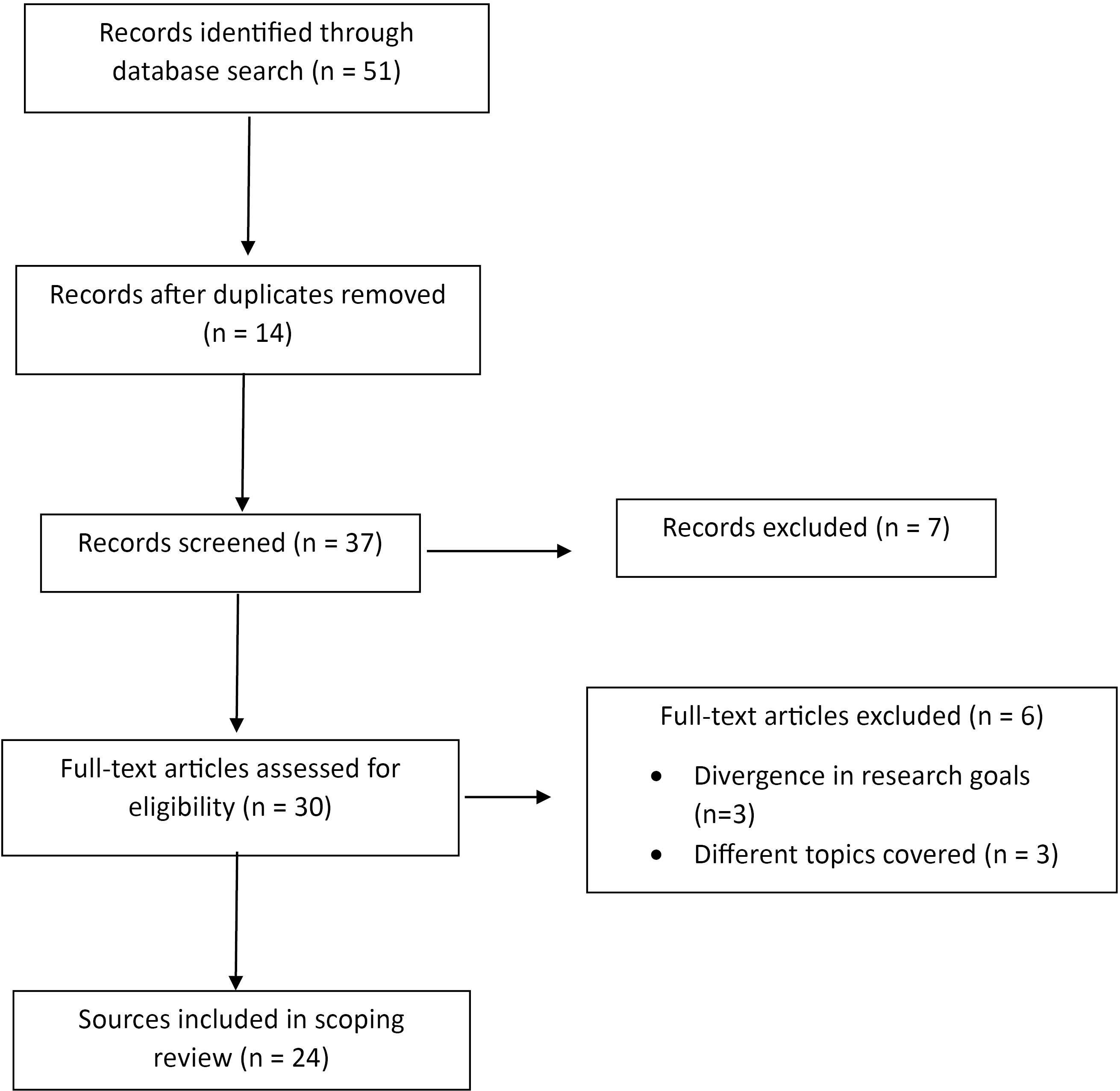

A cumulative total of 51 records were identified across the databases reviewed from the past 41 years since the inception of published sources on community baby showers. 14 of these records were duplicates and ultimately excluded. Among the remaining 37 records, seven of them were subsequently excluded for one or more of the following reasons: (1) did not contain full-text articles; (2) nontarget population; and (3) presented only a study protocol. Thirty remaining full-text articles were examined for inclusion in this scoping review. Six of them were ultimately further excluded for the following reasons: (1) intervention components did not pertain to community baby showers (i.e. divergence in research goals); and (2) focused on a range of considerations outside of infants and their caregivers. 24 of them ultimately met the criteria for the review, delivery, implementation and evaluation of community baby showers representing a public health intervention as depicted in Figure 1.11-34 Ethics or IRB approval was obtained in twelve studies.11-22

Figure 1.

Literature review flowchart

.

Literature review flowchart

Target populations across studies consisted of many caregivers involved in the care of infants (e.g. parents, grandparents, child care providers, etc). Samples of caregivers across studies were diverse across racial, ethic, age, and socioeconomic groups and encompassed a wide range of social determinants of health. All of the studies and secondary sources reviewed involved community engagement. Study designs consisted of the following: two-arm randomized controlled trials, group comparison, cross-sectional, longitudinal, and retrospective ones. Programmatic considerations as part of health education were accounted for in all studies and secondary sources. Several studies involved implementation of greater than one community baby shower and engaged in several methods of community outreach for participation across both traditional and non-traditional sources of media. Sample sizes ranged widely from 35 to ~10 000 across studies.

Goals of community baby showers involved considerations on a continuum from prenatal to postnatal care. Goals across examined sources consisted of the following: building coping skills, heightening support networks, increasing access to resources (e.g. ones in line with the AAP infant safe sleep guidelines and other well-baby supplies), provision of prenatal education that included anticipatory guidance on birthing and parenting, delivery of postnatal education on newborn care, breastfeeding, immunizations and infant safety (e.g. infant safe sleep practices, tobacco cessation), and expanding access to screening via integrated laboratory testing on-site. Education was delivered in the forms of presentations, demonstrations, booths, and workshops. Meals and access to transportation were also integrated as considerations to increase participation in community baby showers among studies and secondary sources.

Deliverers of community baby showers across reviewed sources encompassed many stakeholders and entities including staff across community mental health centers, academic institutions, healthcare providers, paraeducators and many more. Established community partners that participated in community baby showers spanning these sources were diverse and included churches, local businesses, schools, libraries, civic / advocacy groups, healthcare systems, grocery stores, nonprofit organizations, banks, health departments, among more. Funding sources included grants, donations and earnings from fundraisers for the implementation of these community baby showers.

Outcomes assessed across sources included feasibility and acceptability of community baby showers, low birth weight among infants, prematurity, tobacco reduction and cessation among caregivers, initiation of prenatal care, breastfeeding attempts and continuation, increased caregiver knowledge and awareness, and whether community baby showers were in line with caregiver preferences. A consolidated breakdown of each source’s design, SUID related intervention components, and subsequent outcomes can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study characteristics, SUID reduction related components, and findings

|

First author, year, reference, location

|

Study design

|

Participant characteristics (race/ethnicity, typology of caregiver, average age, sample size N)

|

SUID reduction related intervention components

|

SUID reduction related outcomes

|

| Ahlers-Schmidt,20 2014, United States |

Cross-sectional (community engagement) |

Majority were African American women (60.6%), N = 184 |

Community engagement |

None reported |

| Ahlers-Schmidt,32 2019, United States |

18 community baby showers |

Total of 855 pregnant or recently delivered mothers comprised the following racial/ethnicity groups: Non-Hispanic White (52.3%), Hispanic (20.2%), Non-Hispanic Black (18.8%), and Multiracial/other (8.7%); most of the participants (46.9%) had state health insurance |

Engage in health promotion for safe sleep, breastfeeding and smoking cessation; community engagement; participants received a safety approved crib and wearable blanket |

None reported |

| Ahlers-Schmidt,22 2020, United States |

Longitudinal (community engagement) |

Pregnant and recently delivered women, 60.8% of sample consisted of Non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks, majority had state health insurance (58.1%) |

Safe sleep crib demonstration, provision of portable crib, wearable blanket, safe sleep education handouts and materials that included door hangers, door prizes, refreshments, promotion through dissemination of flyers, 10 minute video titled ABCs of Safe Sleep, booths for local programs and resources related to maternal and infant health |

Increased caregiver knowledge and awareness, acceptability of proposed approach |

| Ahlers-Schmidt, 2021,29 United States |

Longitudinal (community engagement) |

146 caregivers of infants represented the following racial/ethnic groups: Hispanic (92.5%), Non-Hispanic White (2.7%), Non-Hispanic Black (2.1%), and Multiracial (1.4%); nearly half of the caregivers were uninsured (52.1%) and approximately one-third had state health insurance (33.6%) |

Provision of prenatal education to expectant mothers and support in navigating present and future care of their infants; promotion through dissemination of flyers; community engagement; participants could elect to receive portable cribs; demonstration of creating a safe sleep crib that involved utilizing a portable crib with a doll in a onesie or sleeper along with a wearable blanket, on its back, and with solely a pacifier; discussions on the recommendation for room sharing with a separate crib, bassinet or portable crib in the primary caregiver’s room as the safest space for an infant to sleep as an evidence-based SIDS-reduction measure; education on breastfeeding and tobacco cessation; participants could receive infant safe sleep education handouts and additional materials (e.g door hangers) in Spanish |

None reported |

| Ahlers-Schmidt, 2021,28 United States |

Community engagement (5 community baby showers - 1 in-person and 4 virtual) |

Pregnant and postpartum women; Non-Hispanic White maternal (in-person: 60.4%; virtual: 68.9%) and paternal caregivers (in-person: 51.0%; virtual: 62.2%) represented the majority across both in-person and virtual community baby showers; majority of participants in the in-person community baby shower group had state health insurance (58.3%) while there was a more even split among state, private, and military health insurance coverage in the virtual community baby shower group (35.1% private, 31.1% state, 27.0% military) |

Provision of education on safe sleep, breastfeeding and tobacco cessation in a rural community during the COVID-19 pandemic; promotion via community engagement; provided portable cribs and wearable blankets; education via demonstrations and presentations on safe sleep, breastfeeding and tobacco cessation; educational materials in the form of digital documents were provided to pregnant and postpartum women |

None reported |

| Ahlers-Schmidt, 2016,19 United States |

Community engagement (3 community baby showers) |

Pregnant women and new mothers; greater non-White pregnant and new mothers than Caucasian mothers (specifically 70% non-White maternal caregivers and 61% paternal caregivers in community baby showers vs. 53% non-White maternal caregivers and 44% of paternal caregivers in clinic baby showers); Non-White participants were from African American, Hispanic and other racial ethnic groups; although majority of caregivers in the community baby shower group had state health insurance (47%), there was a nearly even split of state (39%) and private (41%) health insurance coverage among caregivers in the clinic baby shower group; average age of new and expectant mothers in both community and clinic baby showers was around 26 years of age |

Increase knowledge on the ABCs of safe sleep for present and future caregivers of infants and provide prenatal and breastfeeding education; dissemination of flyers; participants received portable cribs after completing a post-test following each community baby shower; demonstrations on how to set up a safe sleep environment with a portable crib |

None reported |

| Aitken,13 2023, United States |

Randomized controlled trial |

147 teenagers who were pregnant for the first time along with their senior female caregivers; majority of expectant teenage mothers were primarily African American (81.6%) and their average age was nearly 18 years |

Teenager first-time mothers received safety products that included child safety seats, sleep sacks, pack-n-plays, and smoke alarms as their baby shower gifts; education on these products; games and refreshments |

None reported |

| Anderson College of Nursing and Health Professions,25 2021 and 2022, United States |

Cross-sectional (community engagement) |

35 expectant mothers |

Delivered in-services on basic prenatal and baby care; community engagement with healthcare entities; opportunities to win prizes in the form of well-baby supplies which included car seats, pack-n-plays, breast pumps among more; participants received free gift bags |

None reported |

| Arias,24 2007, United States |

Longitudinal (community engagement) |

Breastfeeding and expectant mothers, fathers, grandparents, extended family members, and community members |

Diapers and strollers were provided to participants; offered refreshments to participants; offered child care free of cost; delivered education on breastfeeding advice and encouragement; car seat safety and child maltreatment prevention; community engagement |

None reported |

| Canuso,18 2017, United States |

Community engagement (2 timepoints for interventions) |

Expectant mothers (four African American, one Native American, one White, one Latina); 2 teenage mothers |

Provision of informational support; participants received a bucket or basket filled with baby items or food; health bazaars in the hallways filled with information tables inclusive of brochures and pamphlets that instilled healthy pregnancy messages; luncheon; games for the participants; designated child care spaces for these infants and children during the baby showers |

No pregnant women delivered low birth weight or premature infants; two of the mothers who had previously smoked prior to the community baby shower had reduced their smoking; majority of the mothers had begun prenatal care in their first trimester; all of the mothers except for one had attempted breastfeeding |

| Duffy,27 1994; United States |

Cross-sectional (community engagement) |

Native American adolescent expectant mothers; pregnant women and mothers of newborns |

Education centered on newborn care, immunizations and safety; community engagement; promotion through information sharing at clinic appointments and dissemination of flyers; provision of prizes; new and expectant mothers received pocket calendars to help them keep track of their due dates and immunization schedules for their infants; discussions facilitated by nursing students on newborn care, immunizations and safety following viewing of a video on these topics; pamphlets and demonstrations with dolls and devices (e.g. baby doll, car seat) as part of discussions with participants; a potluck lunch which featured educational baby shower games on content covered during the event; accounting for timing and spiritual needs of the Native American community along with representation of artifacts from the Native American heritage across the decorations for this baby shower |

None reported |

| Ezeanolue,17 2015, Nigeria |

Two-arm cluster randomized design |

Pregnant women and their families; 20 community baby showers across churches; average age of caregivers was ~29 years of age |

Church driven; health education and laboratory testing for HIV, sickle cell genotype, hemoglobin, hepatitis B, malaria and syphilis; community engagement; a pack of essentials that included sanitary pads, clean razor blade, alcohol and gloves was provided to pregnant women |

None reported |

| Ezeanolue,15 2017, Nigeria |

Two-arm cluster randomized design |

Pregnant women and their families, 40 community baby showers across 40 churches; average age of caregivers ~38 years of age |

Church driven; educational game show; integrated laboratory testing for HIV and hemoglobin; refreshments; gift exchange |

None reported |

| Gbadamosi,14 2019, Nigeria |

Retrospective |

9,231 pregnant women and their male partners; majority of pregnant women and their male partners were between 20 to 39 years of age (82%) |

Provided integrated laboratory testing for HIV, hepatitis B, and sickle cell anemia, participation of 80 churches that facilitated baby showers |

None reported |

| Haskins,34 2017, United States |

Cross-sectional (community engagement) |

Nearly 500 participants |

A public health class of students and their professor collaborated with a church to implement the baby shower; a raffle was also implemented and grand prize from the raffle was a year’s worth of diapers |

None reported |

| Itanyi,11 2023; Nigeria |

Exploratory |

Pregnant women, average age: 24 years |

Celebrate pregnancy and provide onsite screening via laboratory testing |

None reported |

| Keeler,23 1982, United States |

Longitudinal (community engagement) |

New and expectant mothers, greater than 1,000 mothers |

Luncheon; literature on pregnancy and child care; identifying stressors, building coping skills and heightening support networks for expectant mothers; providing anticipatory guidance on birthing and parenting; community engagement; promoting community baby showers by disseminating flyers in locations where new and expectant mothers may visit and including information in community newsletters and church bulletins; each mother attending the community baby showers received a gift package that included baby clothes, diapers, baby lotion, toys, and additional items; raffle for new and expectant mothers to win one of 30 door prizes that included strollers, car seats, flowers, and winning the opportunity for a baby’s first haircut; presentations related to prenatal care, nutrition, and health which were delivered by the staff of a community mental health center and additional organizations; designated child care spaces for these infants and children during the baby showers; follow-ups for further supportive resources that included workshops and self-help groups along with developmental screening for their children |

None reported |

| Maurer,26 2018, United States |

Group comparison (community engagement) |

New and expectant mothers that included Nepalese refugees and participants from a rural underserved area of Western Pennsylvania |

Provided prenatal education to expectant mothers and support in navigating present and future care of their infants |

None reported |

| Montandon,12 2021, Nigeria |

80 community baby showers |

Total of 10,056 pregnant women and 6,187 male partners; majority of female caregivers were between 20 to 29 years of age (66.7%); there was a more even split among age groups of paternal caregivers (24.9% between 25 to 29 years, 22.7% between 30 to 34 years of age, 20.2% that were 40 years and older) |

Integrated screening and laboratory testing |

None reported |

| Pharr,21 2016, Nigeria |

Nested cohort study within a 2-arm cluster randomized controlled trial |

Pregnant women and their families |

Church-driven, community engagement, Provision of gifts, refreshments, integrated laboratory testing for HIV, Hepatitis B, and sickle cell anemia |

None reported |

| Sam-Agudu,33 2018, Nigeria |

Two-arm cluster randomized controlled trial |

3,054 pregnant women and 2,498 male partners |

Church driven, HIV testing |

None reported |

| Talla,16 2021, Nigeria |

Cross-sectional |

80 churches in 80 communities; majority of caregivers were between 21 to 31 years of age |

Increasing access to laboratory testing for the community as the basis to support healthier pregnancy outcomes along with health education on early antenatal care, the significance of integrated screening tests for pregnant women, healthy nutrition, skilled birth attendance and immunizations; laboratory testing for HIV, Hepatitis B, and sickle cell anemia |

None reported |

| Thornberry,30 2017, United States |

Community program |

8 community baby showers, pregnant women; parents, grandparents, and foster parents of children 2 years and younger; majority of caregivers were Native American (~30%) followed by Caucasian (~26%) and African American (25%) |

Community engagement; promotion through multimethod in-person and virtual formats; educational presentations on both medical and cultural content pertaining to different dimensions of infant safety (e.g. infant safe sleep, CPR); games and provided gifts; child care; focus on prenatal care, well child care, breastfeeding, and parental care |

None reported |

| Zentz,31 2009, United States |

Health education, community engagement |

Childbearing families; majority of participants were between 19 to 25 years of age (58.11%); participants comprised the following racial/ethnic groups: White (78.41%), African American (12.50%), Hispanic (7.39%), and Other (1.17%) |

Provide prenatal education; community engagement; brochures, fact sheets and videos |

None reported |

Discussion

Across the articles reviewed in this study, there were many that involved heightening knowledge and awareness on infant safety through safe sleep practices, and this education was provided by a range of deliverers that included healthcare providers, community stakeholders, and students. In addition, locations across communities that cast a wider net to reach more caregivers of infants both prenatally and postnatally was focused on in one study. Target populations across studies and secondary sources accounted for primarily maternal caregiver of infants that included expectant mothers prenatally. Community baby showers represented a significant community engagement intervention that ultimately drew in several community stakeholders, thereby increasing access to a range of resources for target populations across studies and secondary sources. Knowledge dissemination was also a focus in the form of presentations delivered by deliverers of community baby showers in several studies. In addition, structural considerations of traditional baby showers (e.g. food, games) were accounted for in several community baby showers implemented. One of the key limitations across studies and secondary sources involved assessing whether there was an impact of community baby showers as an intervention on affecting change in caregiver practices pertaining to infant safe sleep. Although ample educational opportunities in combination with resource provision were an integral part of several community baby showers in several studies and secondary sources in this review, it is unclear how the impact of this community level intervention was in fact measured. Nevertheless, a community baby shower presents an opportunity to promote interagency collaboration, increased access to resources, and heightened knowledge and awareness on infant safety, all of which are potential facilitators of reducing infant mortality across a community.

Target population of caregivers

Notably, only a few of the intended and reached audiences across community baby showers in the studies and secondary sources across this review were paternal caregivers. The target population for many of the studies and secondary sources consisted of new and expectant mothers. It is possible that by delimiting the caregiver population of infants for community baby showers in these studies and secondary sources, this could represent a significant limiting factor of them in casting a wider net to affect change in safe sleep practices and behaviors among caregivers of infants. Future studies could account for messaging across infant safe sleep campaigns (e.g. Safe-to-Sleep campaign) that tailor messages for different caregiver priority groups involved in the care of infants that extend beyond maternal caregivers to include paternal caregivers, grandparents, other extended family members, and child care providers.

Established community partners

In addition, many of the studies and secondary sources in this review demonstrated the strength and wider reach of community baby showers by engaging a range of community stakeholders to participate. Each community stakeholder formed their own contribution towards strengthening engagement, access and education across community baby showers. Furthermore, established partnerships of community stakeholders further enabled interagency collaboration in heightened access to safe sleep resources, diversity of literature, and training in real-time during community baby showers in these studies and secondary sources, thereby providing a window of opportunity for increased education and accessibility for health promotion on a range of modifiable risk factors for SIDS and SUID. It follows that the collective efforts of established community partners could be a measure of sustainability in future implementation of community baby showers over time.

Involvement of faith-based organizations

Notably, faith-based organizations represented a consistent community stakeholder across many of the community baby showers implemented across studies and secondary sources. Libraries, grocery stores, schools, and other community entities were also participants. Churches, synagogues, mosques, temples and other religious spaces oftentimes have a significant impact across a community that can extend into informing health beliefs and practices.35 It is also possible that there will be community residents who are not part of a faith-based organization. However given their presence across a community, engaging them to participate in one or more ways could support extending the reach and impact of community baby showers in the future. Furthermore across the world, many faith-based organizations are already actively involved in providing access to baby supplies and partner with pregnancy centers to secure access to these supplies for caregivers of infants.36 It follows that assuring support and collaboration with faith-based organizations could also be a facilitator of sustainability for community baby showers as a community level intervention for the infant population and their caregivers.

Laboratory testing opportunities

In addition, access to care for laboratory testing was a significant part of several baby showers in Africa across published studies in this review. It is possible that in these studies, assuring laboratory testing could have incentivized participation among caregivers to participate in the community baby showers. This laboratory testing was integrated in nature and extended to include HIV testing. The integrated component of this testing in a large public space could also help destigmatize focus on HIV testing and also present an opportunity for specific screening to identify any risk factors for unsafe pregnancy as the basis to mobilize resources for early intervention and treatment if indicated for the expectant mother. It follows that access to care for laboratory testing in a larger community forum such as a community baby shower could contribute towards a higher screening rate which in turn could strengthen safety in pregnancy, lay the foundation for any intervention if needed, and reduce stigma for HIV testing when integrated with additional high-risk testing for infants and pregnant women.

Recommendations for future research and practice

Taking everything into consideration, it is crucial for future community baby showers to assess the subsequent impact on culture of infant safety and changes in behaviors and practices of caregivers in regard to infant sleep environment. In addition given that many of the deliverers of community baby showers across studies were healthcare providers, it is also imperative to assess changes in clinical practice in the delivery of content on environmental and behavioral risk factors for SIDS and SUID. Most of the education provided in community baby showers across studies were in the form of presentations and demonstrations. It follows that engaging more healthcare providers as credible, primary sources of knowledge dissemination during community baby showers could also lay the foundation for future healthcare providers to also immerse in this role to cast a wider clinical impact across a community that could extend to uninsured and underinsured infants and their caregivers who may not always have access to primary or subspecialty care. Weight, value, and credibility of content delivered by healthcare providers will likely also have a larger educational impact on caregivers of infants as they learn firsthand about a range of practices and information to heighten their awareness on the implications of unsafe sleep environments for infants and the range of resources available as part of SIDS and SUID risk reduction.

In addition, all of the studies and secondary sources in this review implemented community baby showers in the United States and Africa. Community baby showers could benefit countries across the globe given that infant mortality is a worldwide trending issue. It follows that future research could explore the translational impact of implementing community baby showers across continents as the basis to establish its efficacy as a global health intervention.

To assess community level impact, it is crucial to create an evaluation plan to assess the efficacy, acceptability, and feasibility of implementing community baby showers as SIDS reduction measures. One direction for future exploration is to conduct focus groups as part of a summative evaluation to assess uptake of knowledge dissemination, acceptability of the intervention by the community, and feedback on components that could inform improvement for future community baby showers. It is also important to establish training for deliverers of intervention who are actively involved in educational efforts during community baby showers to assure consistency and effectiveness in the dissemination of infant safe sleep content.

Finding ways to continue collaboration with established and new community partners is part of the legacy and sustainability of continued implementation of community baby showers. It follows that planning stages of future community baby showers could enlist support and collaboration among as many community entities as realistically possible. Furthermore, community engagement in implementing community baby showers could further be assessed as an evidence-based community level practice in SIDS and SUID reduction through conducting pilot feasibility studies that examine common elements in engagement and delivery of infant safe sleep content, changes in caregiver practices along with clinical practice pertaining to modifiable risk factors for infant safe sleep over time.

Conclusion

Community baby showers present an optimal opportunity to engage a wide range of community stakeholders in increasing access to a range of resources that will support caregivers of infants in optimizing safer environments for their infants. In addition, community baby showers address a range of modifiable risk factors through mitigating gaps in access to resources and knowledge. It is critical to account for the diversity of caregivers involved in the care of infants. Messaging from the Safe-to-Sleep campaign could be integrated into delivery of messaging for different priority groups of infant caregivers. Access to integrated laboratory testing presented a promising direction for consideration in future community baby showers. Ensuring that there is a way to assess the community level and clinical impact of implementing community baby showers is crucial as the basis to further explore their efficacy as an evidence-based community level intervention in SUID and SIDS reduction. Continued endeavors in the improvement of the design and implementation of community baby showers worldwide will contribute towards addressing the constellation of SUID and SIDS as a leading cause of infant mortality, thereby further contributing towards the larger goal of the World Health Organization and UNICEF in reducing infant mortality worldwide.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data Availability Statement

This study was not formally registered. The analysis plan was not formally pre-registered. There was no de-identified data in this review. There is no analytic code associated with this study. All sources used to conduct the study are available through the following research databases: PubMed, Medline, APA Psych Info, Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, ERIC, EBSCO, and Cochrane Review.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

References

- Müller-Nordhorn J, Schneider A, Grittner U, Neumann K, Keil T, Willich SN. International time trends in sudden unexpected infant death, 1969-2012. BMC Pediatr 2020; 20(1):377. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02271-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459-544. 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1.

- Vincent A, Chu NT, Shah A, Avanthika C, Jhaveri S, Singh K. Sudden infant death syndrome: risk factors and newer risk reduction strategies. Cureus 2023; 15(6):e40572. doi: 10.7759/cureus.40572 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Krous HF, Beckwith JB, Byard RW, Rognum TO, Bajanowski T, Corey T. Sudden infant death syndrome and unclassified sudden infant deaths: a definitional and diagnostic approach. Pediatrics 2004; 114(1):234-8. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.234 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RD, Kinney HC, Guttmacher AE. Only halfway there with sudden infant death syndrome. N Engl J Med 2022; 386(20):1873-5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2119221 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moon RY, Carlin RF, Hand I. Sleep-related infant deaths: updated 2022 recommendations for reducing infant deaths in the sleep environment. Pediatrics 2022; 150(1):e2022057990. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057990 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cribs for Kids. Infant Safe Sleep Education: Preventing and Reducing the Risk of Infant Sleep-Related Deaths. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Cribs for Kids. Available from: https://cribsforkids.org/wp-content/uploads/Program-Education.pdf. Accessed December 24, 2023.

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Safe to Sleep About SIDS and Safe Infant Sleep. Rockville, Maryland: National Institutes of Health. Available from: https://safetosleep.nichd.nih.gov/safesleepbasics/about. Accessed December 24, 2023.

- Menon M, Huber R, West DD, Scott S, Russell RB, Berns SD. Community-based approaches to infant safe sleep and breastfeeding promotion: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2023; 23(1):437. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15227-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- National WIC Association. Health Inequities Leading to SIDS Increase Among Black Infants Must Be Addressed; WIC Is Part of the Solution. Washington, DC: National WIC Association. Available from: https://www.nwica.org/press-releases/. Accessed December 24, 2023.

- Itanyi IU, Iwelunmor J, Olawepo JO, Gbadamosi S, Ezeonu A, Okoli A. Acceptability and user experiences of a patient-held smart card for antenatal services in Nigeria: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023; 23(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s12884-023-05494-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Montandon M, Efuntoye T, Itanyi IU, Onoka CA, Onwuchekwa C, Gwamna J. Improving uptake of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission services in Benue State, Nigeria through a faith-based congregational strategy. PLoS One 2021; 16(12):e0260694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260694 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Aitken ME, Whiteside-Mansell L, Mullins SH, Bai S, Miller BK. Safety baby shower intervention improves safe sleep knowledge and self-efficacy among expectant teens. SAGE Open Nurs 2023; 9:23779608231164306. doi: 10.1177/23779608231164306 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gbadamosi SO, Itanyi IU, Menson WNA, Olawepo JO, Bruno T, Ogidi AG. Targeted HIV testing for male partners of HIV-positive pregnant women in a high prevalence setting in Nigeria. PLoS One 2019; 14(1):e0211022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211022 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ezeanolue EE, Obiefune MC, Yang W, Ezeanolue CO, Pharr J, Osuji A. What do you need to get male partners of pregnant women tested for HIV in resource limited settings? The baby shower cluster randomized trial. AIDS Behav 2017; 21(2):587-96. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1626-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Talla C, Itanyi IU, Tsuyuki K, Stadnick N, Ogidi AG, Olakunde BO. Hepatitis B infection and risk factors among pregnant women and their male partners in the baby shower programme in Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Trop Med Int Health 2021; 26(3):316-26. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13531 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ezeanolue EE, Obiefune MC, Ezeanolue CO, Ehiri JE, Osuji A, Ogidi AG. Effect of a congregation-based intervention on uptake of HIV testing and linkage to care in pregnant women in Nigeria (baby shower): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 2015; 3(11):e692-700. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(15)00195-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Canuso R. Low-income pregnant mothers’ experiences of a peer-professional social support intervention. J Community Health Nurs 2003; 20(1):37-49. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2001_04 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Schunn C, Lopez V, Kraus S, Blackmon S, Dempsey M. A comparison of community and clinic baby showers to promote safe sleep for populations at high risk for infant mortality. Glob Pediatr Health 2016; 3:2333794x15622305. doi: 10.1177/2333794x15622305 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Schunn C, Dempsey M, Blackmon S. Evaluation of community baby showers to promote safe sleep. Kans J Med 2014; 7(1):1-5. doi: 10.17161/kjm.v7i1.11476 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pharr JR, Obiefune MC, Ezeanolue CO, Osuji A, Ogidi AG, Gbadamosi S. Linkage to care, early infant diagnosis, and perinatal transmission among infants born to HIV-infected Nigerian mothers: evidence from the healthy beginning initiative. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 72(Suppl 2):S154-60. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000001051 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Schunn C, Hervey AM, Dempsey M, Blackmon S, Davis B. Redesigned community baby showers to promote infant safe sleep. Health Educ J 2020; 79(8):888-900. doi: 10.1177/0017896920935918 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Keeler K, Swift C. The community baby shower: detroit packages prevention messages to teenage parents. J Prim Prev 1982; 3(1):48-51. doi: 10.1007/bf01326692 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Arias DC. California community baby shower promotes breastfeeding. Nation’s Health. 2007 Oct [cited 2024 Jan 13]. Available from: https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu.

- Anderson College of Nursing and Health Professions Tiny Cubs Community Baby Shower. Alabama Nurse. 2021 Nov [cited 2024 Jan 13]. Available from: https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu.

- Maurer GM, Pallone J. Use of a community baby shower as a diverse approach to cultural and community nursing. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2018; 47(3):S2. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2018.04.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Duffy SA, Bonino K, Gallup L, Pontseele R. Community baby shower as a transcultural nursing intervention. J Transcult Nurs 1994; 5(2):38-41. doi: 10.1177/104365969400500206 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Schunn C, Hervey AM, Torres M, Nelson JEV. Promoting safe sleep, tobacco cessation, and breastfeeding to rural women during the COVID-19 pandemic: quasi-experimental study. JMIR Pediatr Parent 2021; 4(4):e31908. doi: 10.2196/31908 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Schunn C, Hervey AM, Torres M, Cordoba AP. Safe sleep community baby showers to reduce infant mortality risk factors for women who speak Spanish. Sleep Health 2021; 7(5):603-9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2021.07.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thornberry T, Han J, Thomas L. Implementing community baby showers to address infant mortality in Oklahoma. J Okla State Med Assoc 2017; 110(3):136-41. [ Google Scholar]

- Zentz SE, Brown JM, Schmidt NA, Alverson EM. Prenatal showers: educational opportunities for undergraduate students. J Prof Nurs 2009; 25(4):249-56. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2009.01.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Schunn C, Engel M, Dowling J, Neufeld K, Kuhlmann S. Implementation of a statewide program to promote safe sleep, breastfeeding and tobacco cessation to high-risk pregnant women. J Community Health 2019; 44(1):185-91. doi: 10.1007/s10900-018-0571-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sam-Agudu NA, Aliyu MH, Adeyemi OA, Oronsaye F, Oyeledun B, Ogidi AG. Generating evidence for health policy in challenging settings: lessons learned from four prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV implementation research studies in Nigeria. Health Res Policy Syst 2018; 16(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0309-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Haskins J. Students in Brief. Nation’s Health [Internet]. 2017 Oct [cited 2024 Jan 13]. Available from: https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu.

- Galiatsatos P, Lehmijoki-Gardner M, Daniel Hale W. A brief historical review of specific religious denominations: how history influences current medical-religious partnerships. J Relig Health 2016; 55(2):587-92. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0123-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Walters CP, Vernon MM. Faith-based pregnancy center education bridges the maternal health gap. J Christ Nurs 2021; 38(3):180-6. doi: 10.1097/cnj.0000000000000843 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]