BioSocial Health J. 1(1):2-13.

doi: 10.34172/bshj.2

Systematic Review

How does health literacy associated to bio-behavioral and psycho-social outcomes among hemodialysis patients? A systematic review

Leila Zhianfar Data curation, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Haidar Nadrian Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 2, *

Zeinab Javadivala Conceptualization, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 3

Sarisa Najafi Data curation, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 4

Shayesteh Shirzadi Formal analysis, Software, 5

Kamyar Pirehbabi Project administration, Writing – original draft, 3

Ozra Honarpazhouh Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, 3

Somayeh Azimi Investigation, Visualization, 3

Tahyebeh Shirvani Investigation, Visualization, 3

Sakineh Haj Ebrahimi Conceptualization, 6

Devender Bhalla Methodology, Writing – review & editing, 7, 8, 9

Author information:

1Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

2Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

3Department of Health Education & Promotion, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Graduate student in Psychology, Islamic Azad University-Sanandaj Branch, Sanandaj, Iran

5Department of Public Health, Neyshabur University of Medical Sciences, Neyshabur, Iran

6Faculty of Medicine, Department of Urology, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

7Nepal Interest Group of Epilepsy and Neurology (NiGEN), Kathmandu, Nepal

8Sudan League of Epilepsy and Neurology (SLeN)®, Khartoum, Sudan

9Pôle Universitaire Euclide Intergovernmental UN Treaty 49006/49007, Bangui, Central African Republic

Abstract

Introduction:

Although the life expectancy of kidney patients has increased due to hemodialysis (HD), the disease affects their lives in various ways. In this study, we systematically reviewed the relationships between health literacy (HL) and bio-behavioral and psycho-social outcomes in HD patients, to determine the necessary information needed for both micro- and macro-level health decision-making.

Methods:

We performed a comprehensive search for globally eligible studies (from 2000 to 2020) on PubMed, EMBASE, ProQuest, CINAHL Nursing, Cochrane Library and Google scholar. The quality assessment of the studies was performed using the standardized tool of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI).

Results:

Among 29 included studies, 23 and 6 articles were of medium and low quality, respectively, and no article was of high quality. In general, 7210 participants were included in these studies. In total, the lowest, highest and the average level of HL in all researches were reported to be 16%, 76.9% and 31.25% respectively. The findings showed a moderate level of evidence for the relationship of HL with self-care-associated outcomes, disease-related biomarkers, QOL, and perceived social support.

Conclusion:

Despite study heterogeneity and low quality, HL was found to be positively contributed to self-care behaviors, perceived social support and QOL of HD patients. HL seems to play an underpinning role in promoting HD patients’ QOL and its bio-behavioral and psychosocial determinants.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, Health literacy, Quality of life, Self-care, Social support, Systematic review

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

As a chronic, progressive and irreversible disease, end stage renal disease (ESRD) is a worldwide public health concern.1 The most common method of treatment worldwide is hemodialysis (HD).2 According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) report, in 2017, Chronic kidney disease (CKD) resulted in 1.2 million deaths and 35.8 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), worldwide.2 Furthermore, the 2019 GBD report found that CKD was the 18th leading cause of DALYs among the 369 diseases analyzed, compared to 29th leading cause in 1990.3

In a recent study on the outcomes of HD in the patients, the prevalence of fatigue was 72%, and about 66% had a high level of stress (level B or C). In 25% of the patients, recovery time was more than 6 hours after an HD session. 4 In patients receiving dialysis, higher health literacy (HL) is found to be associated with better mental health and quality of life. So, identifying the characteristics of HL may inform specific interventions to improve patient education and support.5

According to WHO, HL is an important skill that patients need to make appropriate health decisions in difficult situations ahead.6 Low level of HL has significant effects on patients’ behavior and has unpleasant consequences,7 including increased risk of hospitalization,8 and death.9 On the other hand, it reduces preventive care and less use of health services.10 In addition, problems caused by inadequate HL in HD patients are also seen in the need for self-care,11 social support,12 and quality of life.13

In HD patients, self-care plays an important role in patients’ adaptation to the disease process, improving quality of life,6 reducing the frequency and duration of hospitalization, reducing treatment costs and patient mortality.14 Improving perceived social support can prevent adverse physiological complications of the disease, increase the level of self-care among the patients, and have a positive effect on a person’s physical, mental and social status, and ultimately lead to increased performance.15 The results of numerous studies have shown that HL affects the general health status of individuals and quality of life related to health.16,17

Planning for modification of physical stressors, improving the level of support for the patients, enhancing the quality of care services provided by the treatment team, upgrading the facilities and equipment and the adoption of an interdisciplinary approach are all believed to improve the care services among in-patients receiving HD treatment.18 In another review study, the relationships between HL and quality of life among patients receiving HD therapy were highlighted.19 However, there is a scarcity in the studies on how HL may be associated to social support, self-care behaviors and QOL among HD patients. Healthcare providers of HD patients should be able to identify the effective causes, the benefits of and the barriers to self-care behaviors, social support and quality of life of the HD patients so that they can reduce costs, disability and mortality rates of these patients through developing proper health promotion programs. Therefore, in this study, the relationships between HL and social support, self-care behaviors and quality of life in patients undergoing HD was systematically reviewed to determine the necessary information needed for both micro- and macro-level health decision-making.

Materials and Methods

Study design and search strategy

The current review was conducted based on JBI Data Extraction Form for Systematic Reviews.20 Studies were searched in the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, PsycInfo, SID, and Magiran. For additional studies, we also used the Google Scholar and CINAHL search engines, conference papers, and grey literature. Citation and reference searches were conducted for eligible articles, and associated authors were checked for further relevant research. Also, we attempted to contact the authors for missing data or compute it using the stated pre/post-intervention values.

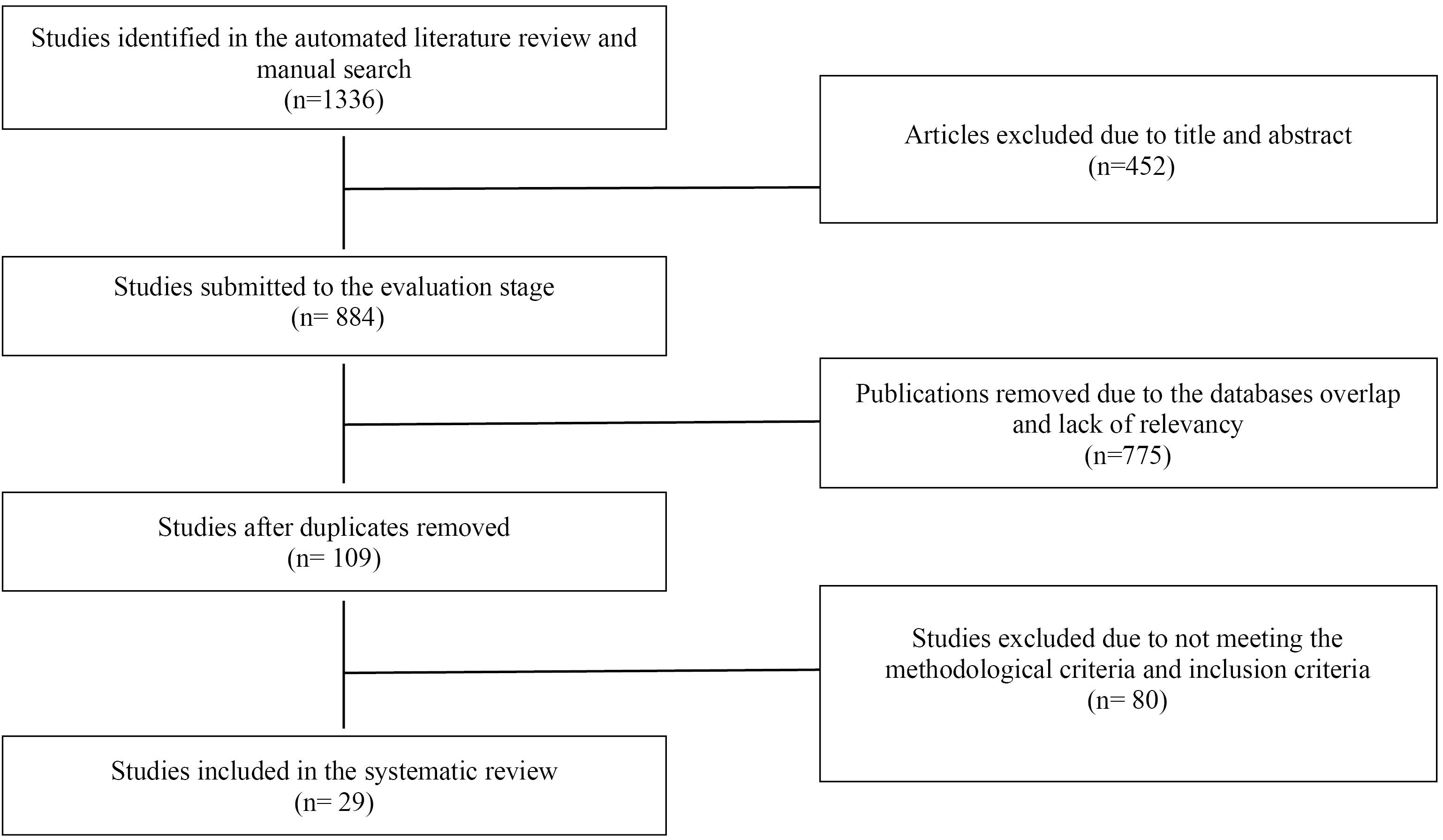

This phase of the study screening yielded a total of 1,336 articles. The selected articles were managed by ENDNOTE X9 software Figure 1. A conclusive combination of keywords related to five main headings of HD, HL, self-care behaviors, social support, and quality of life (as listed in Table S1 of Supplementary file 1) was utilized to retrieve the publications.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the publications screening

.

The PRISMA flow diagram of the publications screening

Study selection and eligibility criteria

The eligibility and exclusion criteria for the study were formulated, a priori, utilizing the PICO (population, intervention, comparisons, and outcomes) framework. The validity of the content was examined and approved by two members of the research team.

Populations referred to HD patients.

Type of study: were delimited to quantitative observational studies including cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies.

Outcomes were any reported relationship between HL and perceived social support, self-care behaviors and quality of life.

Setting. There was no limitation based on the type of settings.

Time. All articles published from January 2000 to April 2020 were considered.

Systematic reviews were not included but used to identify additional eligible studies.

Screening the full-text and synthesis

Two members of the research team, SA and OH, independently conducted the screened studies for inclusion. Disagreements about inclusion were resolved in an iterative process via discussion with a third member of the team (HN), and refinement of the inclusion/exclusion criteria until 100% agreement was achieved. Next, both SA and OH reviewed the full texts of the articles and cross-validated the eligibility based on the inclusion as mentioned above criteria. Subsequently, 29 articles were extracted. Reasons for exclusion are listed in Figure 1.

Data extraction (Encoding results)

We categorized the studies according to authors’ names, year of publication, setting, sample size, mean age of samples, type and aim of study, scales, characteristics of participants (in terms of language and race), research outcomes, and the HL measures (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of the retrieved articles according to authors’ names, year of publication, setting, sample size, mean age of samples, type and aim of study, scales, characteristics of participants, research outcomes, and the health literacy measures among HD patients

|

Author/ year

|

Setting/

year

|

Sample size

|

Age

Mean (SD)

|

Study

design

|

Goal of study

|

Instrument

|

Target group/ race

|

Study outcome

|

Mean of HL

(%)

|

| Green 201321 |

USA

2009-2011 |

260 |

62 |

Cohort |

Prevalence and demographic and clinical population of HL in patients undergoing continuous HD |

REALM |

African-American |

Adherence to dialysis program, emergency visits and ESRD-related hospitalizations |

16% |

Lai

201311 |

Singapore

2013 |

63 |

57/7

(10/1) |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between self-management behaviors and HL in diabetic ESRD patients |

FCCHL |

Chinese, Indian and Malay |

Diabetes self-management behaviors |

51% |

Umeukeje

201612 |

USA

2012-2015 |

377 |

55

(15/3) |

Cross- sectional |

Healthcare providers support patient independence |

s-TOFHLA / BHLS |

American |

Adherence to medication, Serum phosphorus levels, age and racial differences |

56% |

Grubbs

200923 |

USA

2007-2008 |

62 |

52/4

(12/2) |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL and access to kidney transplantation |

s-TOFHLA |

American |

Risk of kidney transplant rejection |

Mean 25.6

Inadequate 32.3% |

Jones

201613 |

Canada

2015 |

106 |

50/07

(12/87) |

Cross- sectional |

HL and knowledge and patient satisfaction before kidney transplantation |

s-TOFHLA |

Canadian, Filipino, South Asian, Black, White and others |

Knowledge of kidney transplantation, and understanding of the need for anti-transplant rejection pills, self-confidence in taking drugs after transplantation |

Mean 32.6 (4.5) |

Qobadi

201424 |

Iran

2014 |

204 |

50/9

10/9 |

Cross- sectional |

HL, negative emotions and self-care |

s-TOFHLA |

Iranian |

Self-care behaviors, depression, anxiety, stress |

inadequate 25%, marginal 9.8%, adequate 65.2% |

Cavanaugh

201025 |

USA

2005-2008 |

480 |

62 |

Cohort |

Relationship between low HL and increased mortality in ESRD patients |

REALM |

American |

Possibility of death due to disease |

32% of patients had limited, 68%

had adequate HL |

Cavanaugh

201526 |

USA

2009-2012 |

150 |

52/2

(13/9) |

Cross- sectional |

HL in HD patients |

REALM, s-TOFHLA, BHLS |

African-American |

Knowledge of HD, knowledge related to kidney disease |

23% |

Green

201127 |

USA

2009-2010 |

260 |

64 |

Cross- sectional |

Demographic characteristics and HL |

REALM |

African-American |

Serological indicators, burden of symptoms, quality of life, mental health and depression |

34% |

Flythe

201728 |

USA

2014-2016 |

154 |

59

(15) |

Cross-sectional |

Relationship between psychosocial factors with 30-day readmission in hospital |

REALM |

Blacks (North Carolina) |

Depression, social support, HL and 30-day readmission to hospital |

49% |

Adeseun

201229 |

USA

2008-2010 |

72 |

51/6 |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL and hypertension and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease |

s-TOFHLA |

African-American |

High blood pressure; Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, lipoprotein (HDL and LDL), BMI, waist to hip ratio and smoking |

21% had limited HL |

Brice

201430 |

USA

2014 |

227 |

- |

Cross- sectional |

Correlation of HL questionnaires in HD patients |

s-TOFHLA, SILS,

TILS |

African-American, white |

- |

129 (55%) adequate, 70 (30%) inadequate, 37 (16%) marginal HL |

Dageforde

201531 |

USA

2012-2013 |

104 |

54

(12) |

Cross- sectional |

Identify patient barriers in evaluating kidney transplantation |

BHLS |

46 percent white |

Perceived knowledge and concern about HL related to kidney transplantation |

Limited (23.1%)

Adequate (76.9%) |

Foster

201132 |

USA

2009 |

311 |

58

(15) |

Cross- sectional |

Evaluation of personal distress preparedness in HD patients |

s-TOFHLA |

African-American, Latin |

Preparing for public and personal disasters related to dialysis and HL |

inadequate 30.3, marginal 19.3,

adequate 50.4

mean 23.1 |

Taylor

201633 |

UK

2011-2013 |

2621 |

58

(47-67) |

Cross- sectional |

Determining the frequency and extent of limited HL in ESRD |

SILS |

British |

Waiting for a transplant, preparing for a transplant, comorbidity, socioeconomic status and language skills |

16% |

Vourakis

201234 |

- |

122 |

54 |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL with phosphate and albumin levels |

- |

22% black |

Phosphate and albumin levels |

- |

Bahadori

201835 |

Iran |

130 |

50% over 60 |

Case study |

Relationship between HL and general health |

HELIA |

47.7% illiterate |

General health |

53.8% inadequate HL |

Martins

201636 |

Portugal |

68 |

66/7 |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between demographic factors and HL |

HLS- EU-Q |

Majority of elderly |

Family relationships, time required for treatment |

61.8% inadequate HL |

Indino

201937 |

South Australia |

42 |

54/4

(13/5) |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL and adherence to treatment (Self-reporting) |

FCCHL |

- |

Adherence to diet, fluids and medication |

High HL (percentage not reported) |

Indino38

2017 |

South Australia |

42 |

54/4

(13/5) |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL with adherence to treatment (Self-reporting) and quality of life |

FCCHL |

- |

Adherence and quality of life |

High HL (percentage not reported) |

Bezzera

201939 |

Brazil |

42 |

59.5% over 41 |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between demographic factors and HL |

STOFHLA |

- |

- |

80.9% inadequate HL |

Stomer

201940 |

Norway |

30 |

67

(13) |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between demographic factors and HL |

HLQ |

187 CKD

(30 HD) |

Depression, loneliness, comorbidity |

14% low HL |

Lim

201941 |

Malaysia |

84 |

- |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL with nutritional knowledge, health beliefs, self-management skills and diet adherence |

HLS- EU-Q |

- |

Nutritional knowledge, health beliefs, self-management skills and diet adherence |

28.5% inadequate HL |

Skoumalova

201942 |

Slovakia |

452 |

63/6 |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL and diet and fluid intake |

HLQ |

- |

Serum phosphate, serum potassium, IDWG |

- |

Stomer

201940 |

Norway |

30 |

67

(13) |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL with quality of life and adherence to long-term treatment |

HLQ |

187 CKD

(30 HD) |

Quality of life and adherence to long-term treatment |

14% low HL |

Lennerling

202043 |

Sweden |

50 |

52 |

Cross- sectional |

HL status |

NVS |

- |

- |

Low HL (20%) |

Griva

202044 |

Singapore |

221 |

59 |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL with depression, annual service use and mortality |

HLQ |

Diabetic HD patients, 58% Chinese |

Depression, annual service use and mortality |

- |

Shayan

201845 |

Iran |

446 |

- |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL and quality of life in diabetic and non-diabetic HD patients |

TOFHLA |

223 diabetic and 223 non-diabetic HD patients |

Quality of life |

Adequate HL in 5.4% diabetic and 17.5% non-diabetic patients |

| Zavacka 202046 |

Slovakia |

542 |

63.6 (14.1) |

Cross- sectional |

Relationship between HL and the decision-making process regarding VA type selection |

HLQ |

542 HD patients |

Higher HL in HD patients is associated with a higher chance of having AVF |

- |

STOFHLA, Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults; REALM, Rapid Evaluation of Adult Literacy in Medicine; REALM-T, transplant-specific version of the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine; BHLS, Brief Health Literacy Screener; NVS, Newest Vital Sign; SILS, Single-Item Literacy Screener; TILS, Two-Item Literacy Screener; HLS- EU-Q, European Health Literacy Questionnaire; FCCHL, Functional, Communicative and Critical Health Literacy; HELIA, Health Literacy Instrument for Adults (Persian version); HLQ, Health Literacy Questionnaire; HD, hemodialysis; HL, health literacy; ESRD, End Stage Renal Disease; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; VA, vascular access

Quality assessment (risk of bias)

Study quality was scored independently by SA and OH guided by a review of tools for assessing the quality of observational studies (JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies).22,47 Studies were assigned scores for inclusion, subjects and setting, exposure measured, objective, confounding factors and strategies to deal with, outcomes measured and appropriate statistical analysis.

Scores were combined to indicate study quality and used to inform grading of studies as low, moderate, and high quality. High quality articles met all criteria. Medium quality articles did not have at least one and at most 4 evaluation criteria.However, this scoring acted as a guide only and grading of studies was decided by discussion between the two researchers, and based on the standard quality evaluation form. The condition of Meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the indicators used to measure the consequences in different studies.

Results

The literature search resulted in a total of 1336 publications. Of these, 452 were excluded due to duplication, and 884 references were based on their titles and abstracts. The remaining 109 studies were retrieved for a detailed evaluation. After the assessment of the full text, a total of 29 studies met our inclusion criteria. Finally, 29 articles satisfied all the review criteria (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the studies

The essential characteristics of the studies are shown in Table 1. The studies were published between 2000 and 2020. In total, 7210 patients were studied. Of 29 studies, 26 were cross-sectional surveys. Except for 6 articles from developing countries [Singapore (2), Iran (2), Brazil (1), Malaysia (1)], 21 articles were from developed countries. Eleven studies were conducted in the United States. Ethnicity data were unavailable for 12 studies (total of 1565 patients),35-45,48 and age data were unavailable for three studies (total of 757 patients).30,41,45

Methodological quality

The quality of studies was assessed by two authors with JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies. It was graded as low for 6 studies and moderate for 23 studies. The details of the methodological quality information of the studies were presented in Table S2 of Supplementary file 1.

Health literacy rate

In total of 29 studies, the lowest and the highest HL rates were 16% among HD patients with African American ethnicity and 76.9% among White Americans. Among all patients, the average of total HL was calculated to be 31.25%. The highest percentage of HL was reported in two studies from the United States, which were 76.9%31 and 68%,25 and were performed on HD patients with a mean age of 52 and 62 years. From the remaining data, in African-American descent49-51 the average HL was 27.25%, in Americans13,23,25-28,31,33,52,53 32.5% and in other races11,29,30,32,54 were 27.3%. In an Iranian study in 2015, the level of insufficient-borderline and sufficient HL was reported as 34.8% and 65.2%, respectively,24 and in another study in 2021,55 the mean score of patients’ health literacy was 77.40±12.94. In the studies conducted in Portugal, Brazil, Norway, Malaysia and Sweden, the rate of insufficient HL was reported to be 61.8%, 80.9%, 14%, 28.5%, and 20%, respectively.36,39-41,43 The mean age of participants was 57.3 years old (only 8 studies over 60).

Table 2 defines low health literacy and its relationship to self-care behaviors, perceived social support, quality of life and etc. in hemodialysis patients.

Table 2.

Health literacy and its relationship to bio-behavioral and psycho-social outcomes among hemodialysis patients in the retrieved articles

|

Author / Year

|

Self-care behaviors

|

Adherence to treatment

|

social support

|

Use of health services

|

Disease-related outcomes and biomarkers

|

Quality of life

|

Green

2013,21 |

|

Increased incidence of incomplete dialysis treatment; missed (0.6% vs 0.3%; adjusted IRR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.10-4.17) |

|

Increase emergency visits (annual visits, 1.7 vs 1.0; adjusted IRR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.01-1.86)Increased hospitalization due to ESRD (annual hospitalizations, 0.9 vs 0.5; adjusted IRR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.03-2.34) |

|

|

Lai

2013,11 |

Communication, critical and overall HL was associated with diabetes self-management (r = 0.40; P = 0.001, r = 0.32; P = 0.011 and r = 0.35; P = 0.005, respectively) |

|

|

|

|

|

Umeukeje

2016,22 |

|

Lack of connection with adherence to treatment |

|

Lack of connection with the use of health care |

Lack of correlation with serum phosphorus levels |

|

Grubbs

2009,23 |

|

|

|

|

Increased risk of transplant rejection (adjusted hazard

ratio [AHR] 0.22; 95% CI 0.08, 0.60; P = 0.003 |

|

Jones

2016,13 |

Relationship between higher HL and knowledge about kidney transplantation (r = 0.52; P = 0.05) |

Relationship between HL and understanding the need to take anti-transplant rejection pills (r = 0.38; P = 0.05) and self-confidence in taking drugs after transplantation (r =

0.32; P= 0.05) |

|

|

|

|

Qobadi

2015,24 |

Relationship between inadequate HL and poor self-care behaviors (b = 0.043; P < 0.001) |

|

|

|

|

Relationship between HL and depression (b = -0.15; P < 0.001), anxiety (b = -0.11; P < 0.001) and stress level (b = -0.10; P < 0.001) |

Cavanaugh

2010,25 |

|

|

|

|

Increased risk of death from disease due to limited HL (HR 1.54; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.36) |

|

Cavanaugh

2015,26 |

Relationship between HL and knowledge of HD (0.43; 95% CI: 0.28–0.55); P < 0.001) and knowledge of kidney disease (0.41; 95% CI: 0.27–0.54) |

|

|

|

|

|

Green

2011,27 |

|

|

|

|

Lack of relationship between limited HL and serological indicators and burden of disease symptoms |

Lack of connection between limited HL and quality of life, mental health and depression |

Flythe

2017,28 |

|

|

Increased chances of 30-day readmission in hospital and poor social support by controlling confounding variables 2.57 (1.10–5.91) |

Increased chances of 30-day readmission in hospital and limited HL by controlling confounding variables 2.20 (0.99–4.97) |

|

Increased chance of 30-day readmission in hospital and depressive symptoms by controlling confounding variables 2.33 (1.02–5.15) |

Adeseun

2012,29 |

Lack of relationship between HL and smoking |

|

|

|

Relationship between adequate HL and low blood pressure (systolic and diastolic blood pressure); No relationship between HL and lipoprotein (HDL and LDL) levels, BMI, waist to hip ratio |

|

Brice

2014,30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dageforde

2015,31 |

Relationship between HL and adequate knowledge with the stage after kidney transplantation in comparison with limited HL (90% vs. 34%; P < 0.001) |

|

|

|

|

|

Foster

2011,32 |

Lack of connection between HL and preparedness for general disasters and disasters related to dialysis |

|

|

|

|

|

Taylor

2016,33 |

|

|

|

Relationship between limited HL and socioeconomic status |

Relationship between limited HL and comorbidities and poor English language skills |

|

Vourakis

2012,34 |

|

|

|

|

Association of limited HL with low phosphate and lack of association with albumin |

|

Bahadori

2018,35 |

|

|

|

|

|

Relationship between HL and general health status |

Martins

2016,36 |

|

|

Higher HL in patients with better family relationships |

Relationship between HL and the time required for treatment |

|

|

Indino

2019,37 |

|

Relationship between higher HL and improved adherence to diet (OR 3.66; 95% CI 1.08-12.43, P = 0.03), fluid restriction (OR 4.92; 95% CI 1.13-21.35, P = 0.03) and medication (OR 11.88; 95% CI 2.26-62.44, P = 0.003) |

|

|

|

|

Indino

2017,38 |

|

Relationship between higher HL and improved adherence |

|

|

|

Relationship between HL with psychological and environmental domains of quality of life |

Bezzera

2019,39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stomer

2019,40 |

|

Relationship between some subscales of HL and medication |

Relationship between some HL subscales and living alone |

|

Relationship of some HL subscales and comorbidities |

Relationship between some HL subscale and depression |

Lim

2019,41 |

Relationship between HL and nutritional knowledge (r = 0.704), perceived benefits (r = 0.408), perceived barriers (r = -0.435), self-efficacy (r = 0.531) and self-management skills (r = 0.691) |

Relationship between HL and diet adherence with control of confounders (b = 0.899, P = 0.004) |

|

|

|

|

Skoumalova

2019,42 |

|

Relationship between HL with diet and fluid intake |

|

|

Relationship between low HL and high serum phosphate (OR:0.77; 95% CI: 0.63–0.94), high non-adherence (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.62–0.89) and overhydrated (OR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.65–0.94) |

|

Stomer

2019,40 |

|

Relationship between some subscales of HL and adherence to long-term treatment |

|

|

|

Higher quality of life in groups with higher HL |

Lennerling

2020,43 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Griva

2020 44 |

|

|

|

Relationship between some subscales of HL and the rate of hospitalization |

Correlation of some HL subscales with mortality rate |

|

Shayan

2018,45 |

|

|

|

|

Less HL in diabetic than non-diabetic patients |

Lack of connection between HL and quality of life |

| Zavacka 2020,46 |

Relationship between some subscales of HL with vascular access |

|

|

|

|

|

IRR, incidence rate ratio; HL, health literacy

Health literacy and self-care associated outcomes

Six studies11,25,31,51-53 investigated the relationship between HL and self-care management and their related cognitive factors in HD patients. HL was significantly associated to the promotion of perceived self-efficacy and self-care behaviors,52 knowledge related to kidney,26 and self-efficacy and self-management skills,41 knowledge related to the next stage of kidney transplantation13,31 and self-management of diabetes in HD patients.11

Nine out of 29 studies examined the relationship between HL and treatment adherence and its related dimensions in the patients. Higher HL was related with improved adherence to diet (OR 3.66; 95% CI 1.08-12.43, P = 0.03), and fluids (OR 4.92; 95% CI 1.13-21.35, P = 0.03). Higher functional HL was associated with less adherence difficulties (per 1-point higher: −1.79 [95% (CI): −2.59 to −0.99]).56

Five studies examined the relationship between HL and the use of healthcare services and its related aspects in patients undergoing HD. Low levels of HL were significantly contributed to increased emergency visits (annual visits, 1.7 vs 1.0; adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.01-1.86) and hospitalization due to ESRD (annual hospitalizations, 0.9 vs 0.5; adjusted IRR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.03-2.34).21 Low HL was also associated to low socioeconomic status of the patients,33 and increase in the duration of treatment.44

Health literacy and perceived social support

Four studies12,27,33,44 examined the relationship between HL and perceived social support in HD patients. According to the findings, the patients with higher levels of HL missed fewer treatment sessions, less hospitalized, and less dependent on others. There was also a direct relationship between HL and the level of family support.33 Poor social support during hospitalization may be risk factors for readmission in dialysis patients. Our findings suggest that hospital-based assessments of psychosocial factors may improve readmission risk prediction.44 Female gender, low education level, more prescribed medications, and depressive symptoms were associated with lower HL. Living alone and the presence of co-morbidities were more common in people with less HL.27 Patients with higher monthly income show better HL in all dimensions.23

HL and disease-related biomarkers

Twelve studies examined the relationship between HL and at least one of the bio-makers and disease-related outcomes in HD patients. In Grubbs study, in the U.S., low HL was associated with an increased risk of renal transplant rejection (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR] 0.22; 95% confidence interval 0.08, 0.60; P = 0.003).23 In Cavanaugh study, in the U.S., limited HL increased the risk of dying from the disease (HR 1.54; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.36).25 Limited HL was also associated with co-morbidity, high serum phosphate, and over-hydration.42

Health literacy and health-related quality of life

In our review, 8 studies13,21,23,25,28,30,32,54,57 were found on the relationship between HL and quality of life, health status and their associated factors, such as depression, and stress levels in HD patients. In Qobadi study, in Iran, HL was associated with higher levels of depression (b = -0.15; P < 0.001), anxiety (b = -0.11; P < 0.001), and stress (b = -0.10; P< 0.001).52 In two other studies, adequate HL was found to be effective in controlling hypertension and increasing life expectancy.21,30 Patients with good HL levels were found to be with higher quality of life.58

Discussion

In this study, we systematically reviewed the studies that investigated the contribution of HL to some bio-behavioral and psychosocial outcomes among patients under HD. Our systematic review on the literature published until 2020 showed the significant expansion of HLresearch in HD patients. A total of 29 studies published since 2000 wereidentified, within which 7188 patients were studied.In terms of geographical variation of studies, only 6 studies were conducted in developing countries and, 21 articles were performed in developed countries. More than one third of the research was conducted in the United States, which represents this country as a pioneer in considering HL as a social determinant of health among HD patients.

The average score for HL in all studies was 31.25%. In a systematic study, Taylor et al59 reviewed 29 studies that investigated the associations of HL to patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease in the United States. They reported that limited HL affects 25% of people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and may reduce self-management skills leading to poorer clinical outcomes. By disproportionately affecting people of low socioeconomic status and nonwhite ethnicity, limited HL may increase health disparities. By comparing the findings of this study with HL interventions in chronic conditions60 it can be concluded that HL optimization interventions appear to be important for improving health outcomes in chronic conditions (with diabetes and heart disease as the most targeted chronic conditions). To ensure the development of cumulative knowledge in this field, we need theory-based interventions, with consistency in methods, and more appropriate and comprehensive measures to understand the complexity of interventions.

HL was identified to have substantial implications for improving several socio-psychological and bio-behavioral outcomes in HD patients. In the present study, HL was significantly associated with the promotion of perceived self-efficacy, 41 self-care behaviors, 52 knowledge related to kidney and HD,26 knowledge related to the post-kidney transplant stage, 13,31 and diabetes self-management11 in dialysis patients. Also, higher HL was associated to improved adherence to diet, fluids, and medication.13,41,42,48,56 Results of previously published systematic reviews61-63 have shown that self-care interventions have been able to greatly reduce the symptoms of the disease in the patients with chronic diseases. Self-efficacy provides a useful framework for understanding and predicting adherence to self-care behaviors and the effectiveness of self-management in the treatment of the chronic diseases, like kidney disease. 64 In other words, HL is reported as an important factor in determining self-care indicators, including adherence to medication, diet and exercise. Inadequate HL is also reported as an important barrier to patients’ adherence to treatment instructions.65

The findings of our review also revealed remarkable contributions between patients’ HL and various aspects of perceived social support,28,36,40 and the use of health services.12,21,33,44 HD patients in developing and underdeveloped countries are generally facing added burden to their illness, due to inherent healthcare insufficiencies, financial costs, and inadequacies in social support and health services.66 We also identified direct associations between the level of HL of the patients and their level of family support.36 The relations between the patients and their social environment, particularly family and society, provide a fundamental basis for social support, which strengthens the mechanism of coping with the chronic disease.67 The family members’ engagement level and enrichment of their perception, awareness and self-efficiency in providing the expected support to a patient with ESRD has been proven in a recent study.68 The role of family support of an ill member of the family in embracing health related advantages was also pinpointed in several previous studies.69-71

As a social determinant of health, HL is reported to have a significant effect on the quality of life of patients with chronic diseases, including HD patients.5,72 Sorensen et al. found that low HL was associated to poor quality of life in HD patients, which might be due to reduced accessibility and less use of medical care, and increased stress load, as a results of increased daily life challenges, poor self-management and decreased self-efficacy.73 Therefore, HL should be considered as an underpinning factor that facilitates the practice of health behaviors, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and ultimately improvement in the patients’ quality of life. In our review, the effect of HL on patients’ quality of life was found to be more remarkable than its effect on HD patients’ self-care behaviors and perceived social support, which might be due to its synergistic effect on improving self-care and social support in these patients.

Limitations

Due to the weakness of the articles in providing reliable and definite indicators for all studied variables, meta-analysis was not possible. Many articles were identified with poor reporting, due to the lack of clarity in the instruments they used to assess HL, and the process they applied to assess it in practice. A high level of heterogeneity was also identified in the outcome variables in various studies. Therefore, it was not possible for us to provide a definitive and exact answer for the relationships of HL with self-care behaviors, perceived social support and quality of life in HD patients.

Conclusion

According to the results of our systematic review, HL was positively contributed to self-care behaviors, perceived social support and quality of life of the patients undergoing HD. HL seems to play an underpinning role in promoting HD patients’ QOL and its bio-behavioral and psychosocial determinants, which represents this health determinant as a core category that should be kept in mind while planning for health promotion programs among HD patients. Health policymakers, health practitioners and healthcare providers of the HD patients should take into account HL during the development of practical guidelines for patients’ health promotion and QOL improvement. In future research, there should be a focus on investigating the contribution of HL to disease-related biomarkers, such as serum phosphate and albumin. It is also recommended to consider HL while designing cohort, case-control and/or longitudinal studies aiming at the provision of stronger evidence for such associations.

Competing Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

This research was ethically approved in Ethics Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Ethics Code: IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1398.294).

Funding

This research received a grant from the Iranian Evidence-Based Medicine Research Center (grant number: 62473).

Supplementary Files

Supplementary file 1 contains Tables S1 and S2.

(pdf)

References

- Cinar S, Unsal Barlas G, Ecevit Alpar Ş. Stressors and coping strategies in hemodialysis patients. Pak J Med Sci 2009; 25(3):447-52. [ Google Scholar]

- GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020; 395(10225):709-33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30045-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396(10258):1204-22. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30925-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guerraoui A, Prezelin-Reydit M, Kolko A, Lino-Daniel M, de Roque CD, Urena P. Patient-reported outcome measures in hemodialysis patients: results of the first multicenter cross-sectional ePROMs study in France. BMC Nephrol 2021; 22(1):357. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02551-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dodson S, Osicka T, Huang L, McMahon LP, Roberts MA. Multifaceted assessment of health literacy in people receiving dialysis: associations with psychological stress and quality of life. J Health Commun 2016; 21(Suppl 2):91-8. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1179370 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 2004; 13(2):299-310. doi: 10.1023/b:qure.0000018486.91360.00 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. Subjective change and its consequences for emotional well-being. Motiv Emot 2000; 24(2):67-84. doi: 10.1023/a:1005659114155 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pignone M, DeWalt DA, Sheridan S, Berkman N, Lohr KN. Interventions to improve health outcomes for patients with low literacy A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2005; 20(2):185-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40208.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sayin A, Mutluay R, Sindel S. Quality of life in hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and transplantation patients. Transplant Proc 2007; 39(10):3047-53. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.09.030 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care 2002; 40(5):395-404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lai AY, Ishikawa H, Kiuchi T, Mooppil N, Griva K. Communicative and critical health literacy, and self-management behaviors in end-stage renal disease patients with diabetes on hemodialysis. Patient Educ Couns 2013; 91(2):221-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.018 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Umeukeje EM, Merighi JR, Browne T, Wild M, Alsmaan H, Umanath K. Health care providers’ support of patients’ autonomy, phosphate medication adherence, race and gender in end stage renal disease. J Behav Med 2016; 39(6):1104-14. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9745-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jones J, Rosaasen N, Taylor J, Mainra R, Shoker A, Blackburn D. Health literacy, knowledge, and patient satisfaction before kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc 2016; 48(8):2608-14. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.07.018 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Browne T, Merighi JR. Barriers to adult hemodialysis patients’ self-management of oral medications. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 56(3):547-57. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Yang JP, Shiu CS, Simoni JM, Xiao S, Chen WT. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey among people living with HIV/AIDS in China. Appl Nurs Res 2015; 28(4):328-33. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.03.006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Javadzade SH, Sharifirad G, Radjati F, Mostafavi F, Reisi M, Hasanzade A. Relationship between health literacy, health status, and healthy behaviors among older adults in Isfahan, Iran. J Educ Health Promot 2012; 1:31. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.100160 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, Huang Z, Zhang D, Deng Q. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013. JAMA 2017; 317(24):2515-23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7596 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hashemi MS, Irajpour A, Abazari P. Improving quality of care in hemodialysis: a content analysis. J Caring Sci 2018; 7(3):149-55. doi: 10.15171/jcs.2018.024 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu YH, Seylania K, Bahramnezhad F. The relationship between health literacy and quality of life among hemodialysis patients: an integrative review. Hum Antibodies 2020; 28(1):75-81. doi: 10.3233/hab-190394 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015; 4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Green JA, Mor MK, Shields AM, Sevick MA, Arnold RM, Palevsky PM. Associations of health literacy with dialysis adherence and health resource utilization in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2013; 62(1):73-80. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.12.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross sectional studies. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute. 2016.

- Grubbs V, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Hsu CY. Health literacy and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4(1):195-200. doi: 10.2215/cjn.03290708 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Qobadi M, Besharat M, Rostami R, Rahiminezhad A, Pourgholami M. Health literacy, negative emotional status, and self-care behaviors in dialysis. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health 2015; 17(1):46-51. [ Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh KL, Wingard RL, Hakim RM, Eden S, Shintani A, Wallston KA. Low health literacy associates with increased mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21(11):1979-85. doi: 10.1681/asn.2009111163 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh KL, Osborn CY, Tentori F, Rothman RL, Ikizler TA, Wallston KA. Performance of a brief survey to assess health literacy in patients receiving hemodialysis. Clin Kidney J 2015; 8(4):462-8. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv037 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Green JA, Mor MK, Shields AM, Sevick MA, Palevsky PM, Fine MJ. Prevalence and demographic and clinical associations of health literacy in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6(6):1354-60. doi: 10.2215/cjn.09761110 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Flythe JE, Hilbert J, Kshirsagar AV, Gilet CA. Psychosocial factors and 30-day hospital readmission among individuals receiving maintenance dialysis: a prospective study. Am J Nephrol 2017; 45(5):400-8. doi: 10.1159/000470917 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Adeseun GA, Bonney CC, Rosas SE. Health literacy associated with blood pressure but not other cardiovascular disease risk factors among dialysis patients. Am J Hypertens 2012; 25(3):348-53. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.252 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brice JH, Foster MB, Principe S, Moss C, Shofer FS, Falk RJ. Single-item or two-item literacy screener to predict the S-TOFHLA among adult hemodialysis patients. Patient Educ Couns 2014; 94(1):71-5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dageforde LA, Box A, Feurer ID, Cavanaugh KL. Understanding patient barriers to kidney transplant evaluation. Transplantation 2015; 99(7):1463-9. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000000543 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Foster M, Brice JH, Shofer F, Principe S, Dewalt D, Falk R. Personal disaster preparedness of dialysis patients in North Carolina. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6(10):2478-84. doi: 10.2215/cjn.03590411 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Taylor DM, Bradley JA, Bradley C, Draper H, Johnson R, Metcalfe W. Limited health literacy in advanced kidney disease. Kidney Int 2016; 90(3):685-95. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.05.033 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vourakis AC, Mitchell CR, Bhat P. Health literacy is associated with higher serum phosphorus levels in urban hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2012; 59(4):A24. [ Google Scholar]

- Bahadori M, Najari F, Alimohammadzadeh K. The relationship between health literacy and general health level of hemodialysis patients: a case study in Iran. Nephrourol Mon 2018; 10(3):e66034. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.66034 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Martins C, Campos S, Duarte J, Martins R, Silva D, Chaves C. Health literacy among dialysis patients. J Econ Soc Dev. 2016:270-5. Bebin in ketabe.

- Indino K, Sharp R, Esterman A. The effect of health literacy on treatment adherence in maintenance haemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. Ren Soc Australas J 2019; 15(1):11-8. doi: 10.33235/rsaj.15.1.11-18 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Indino K. The effect of health literacy on self-reported treatment adherence and quality of life in maintenance haemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. Ren Soc Australas J 2017; 13:124. [ Google Scholar]

- de Melo Bezerra JN, de Oliveira Lessa SR, do Ó MF, de Andrade Luz GO, de Oliveira Tito Borba AK. Health literacy of individuals undergoing dialysis therapy. Texto Contexto Enferm 2019; 28:e20170418. doi: 10.1590/1980-265x-tce-2017-0418 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stømer UE, Gøransson LG, Wahl AK, Urstad KH. A cross-sectional study of health literacy in patients with chronic kidney disease: associations with demographic and clinical variables. Nurs Open 2019; 6(4):1481-90. doi: 10.1002/nop2.350 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lim JH, Zakaria NF, Chinna K, Karupaiah T, Daud Z. SUN-313 exploring the relationships between health literacy, dietary adherence and its mediators in hemodialysis patients in Malaysia. Kidney Int Rep 2019; 4(7 Suppl):S290. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.05.720 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Skoumalova I, Kolarcik P, Madarasova Geckova A, Rosenberger J, Majernikova M, Klein D. Is health literacy of dialyzed patients related to their adherence to dietary and fluid intake recommendations?. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16(21):4295. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214295 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lennerling A, Petersson I, Andersson UM, Forsberg A. Health literacy among patients with end-stage kidney disease and kidney transplant recipients. Scand J Caring Sci 2021; 35(2):485-91. doi: 10.1111/scs.12860 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Griva K, Yoong RK, Nandakumar M, Rajeswari M, Khoo EY, Lee VY. Associations between health literacy and health care utilization and mortality in patients with coexisting diabetes and end-stage renal disease: a prospective cohort study. Br J Health Psychol 2020; 25(3):405-27. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12413 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shayan N, Ozcebe H, Arici M. FP676 evaluation of health literacy (HL) and quality of life (QOL) in hemodialysis patients: is it different in diabetic patients?. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018; 33(Suppl 1):i273. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy104.FP676 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zavacka M, Skoumalova I, Geckova AM, Rosenberger J, Zavacky P, Pobehova J. Does health literacy of hemodialyzed patients predict the type of their vascular access? A cross-sectional study on Slovak hemodialyzed population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(2):675. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020675 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. 10.46658/jbimes-20-08.

- Elisabeth Stømer U, Klopstad Wahl A, Gunnar Gøransson L, Hjorthaug Urstad K. Health literacy in kidney disease: associations with quality of life and adherence. J Ren Care 2020; 46(2):85-94. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12314 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sit JW, Wong TK, Clinton M, Li LS, Fong YM. Stroke care in the home: the impact of social support on the general health of family caregivers. J Clin Nurs 2004; 13(7):816-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00943.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brunner LS, Suddarth D. Brunner & Suddarth’s Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing. LWW; 2010.

- McNaughton CD, Kripalani S, Cawthon C, Mion LC, Wallston KA, Roumie CL. Association of health literacy with elevated blood pressure: a cohort study of hospitalized patients. Med Care 2014; 52(4):346-53. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000101 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ibelo U, Green T, Thomas B, Reilly S, King-Shier K. Ethnic Differences in Health Literacy, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Management in Patients Treated With Maintenance Hemodialysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2022; 9:20543581221086685. doi: 10.1177/20543581221086685 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Miller-Matero LR, Hyde-Nolan ME, Eshelman A, Abouljoud M. Health literacy in patients referred for transplant: do patients have the capacity to understand?. Clin Transplant 2015; 29(4):336-42. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12519 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pagels AA, Söderkvist BK, Medin C, Hylander B, Heiwe S. Health-related quality of life in different stages of chronic kidney disease and at initiation of dialysis treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012; 10:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-71 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mollaoğlu M, Başer E, Candan F. Examination of the relationship between health literacy and health perceptions in hemodialysis patients. J Renal Endocrinol 2021; 7:e11. doi: 10.34172/jre.2021.11 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Inanaga R, Toida T, Aita T, Kanakubo Y, Ukai M, Toishi T. et al. Trust, Multidimensional Health Literacy, and Medication Adherence among Patients Undergoing Long-Term Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000392.

- Murali K, Mullan J, Roodenrys S, Lonergan M. Comparison of health literacy profile of patients with end-stage kidney disease on dialysis versus non-dialysis chronic kidney disease and the influencing factors: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020; 10(10):e041404. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041404 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jafari A, Zadehahmad Z, Armanmehr V, Talebi M, Tehrani H. The evaluation of the role of diabetes health literacy and health locus of control on quality of life among type 2 diabetes using the Path analysis. Sci Rep 2023; 13(1):5447. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-32348-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Taylor DM, Fraser S, Dudley C, Oniscu GC, Tomson C, Ravanan R. Health literacy and patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018; 33(9):1545-58. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx293 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Larsen MH, Mengshoel AM, Andersen MH, Borge CR, Ahlsen B, Dahl KG. “A bit of everything”: health literacy interventions in chronic conditions - a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2022; 105(10):2999-3016. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.05.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cochran J, Conn VS. Meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes following diabetes self-management training. Diabetes Educ 2008; 34(5):815-23. doi: 10.1177/0145721708323640 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sherifali D, Bai JW, Kenny M, Warren R, Ali MU. Diabetes self-management programmes in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2015; 32(11):1404-14. doi: 10.1111/dme.12780 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heinrich E, Schaper NC, de Vries NK. Self-management interventions for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Eur Diabetes Nurs 2010; 7(2):71-6. doi: 10.1002/edn.160 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rahimi M, Izadi N, Khashij M, Abdolrezaie M, Aivazi F. Self-efficacy and some of related factors in diabetic patients. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci 2015;22(6):1665-72. [Persian].

- Reisi M, Mostafavi F, Javadzade SH, Mahaki B, Sharifirad G. Assessment of some predicting factors of self-efficacy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Iran J Endocrinol Metab 2015;17(1):44-52. [Persian].

- Wetmore JB, Collins AJ. Meeting the world’s need for maintenance dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26(11):2601-3. doi: 10.1681/asn.2015060660 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Kane RL, Xu D, Meng Q. Health literacy as a moderator of health-related quality of life responses to chronic disease among Chinese rural women. BMC Womens Health 2015; 15:34. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0190-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhianfar L, Nadrian H, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Espahbodi F, Shaghaghi A. Effectiveness of a multifaceted educational intervention to enhance therapeutic regimen adherence and quality of life amongst Iranian hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial (MEITRA study). J Multidiscip Healthc 2020; 13:361-72. doi: 10.2147/jmdh.s247128 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mi T, Li X, Zhou G, Qiao S, Shen Z, Zhou Y. HIV disclosure to family members and medication adherence: role of social support and self-efficacy. AIDS Behav 2020; 24(1):45-54. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02456-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Damodaran S, Huttlin EA, Lauer E, Rubin E. Mental health trainee facilitation of sibling support groups: understanding its influence on views and skills of family-centered care. Acad Psychiatry 2020; 44(3):305-10. doi: 10.1007/s40596-019-01150-7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Park Y, Jang EJ, Lee YJ. Intensive care unit length of stay is reduced by protocolized family support intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2019; 45(8):1072-81. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05681-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Erfani Khanghahi M, Ebadi Fard Azar F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the quality of life in Iranian elderly people using LEIPAD questionnaire. Payavard Salamat 2018;11(5):588-97. [Persian].

- Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012; 12:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]